Arts of Rebellion: 5 Impactful Works By Women

Post-election, the art I've been thinking about most

Election night 2016 was laden with shock and rage and incredulous phone calls. Since then, a creeping dread has lingered among progressive women, a suspicion that misogyny in American runs much deeper than we were raised to believe. This week, like the denouement of a slow-moving horror film, our fears were confirmed: the call has been coming from inside the house. Already, our attempts to process are underway, in podcasts, and think pieces, and moments of quiet desperation.

I have yet to feel the shock and rage I did in 2016, although I know it will come. For now, my mind has spun, unbidden, around creative works by women, the acts of artistic rebellion that underscore why authoritarian governments punish artists. I reread Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wallpaper,” her main character driven to insanity by a health protocol imposed on her by men. I blasted more Ani DeFranco than I have in years. And I’ve reflected at length on several specific works by women, most of which I’ve seen in exhibitions over the past few years. Here are the five I’ve thought of most, and why each one resonates in this moment.

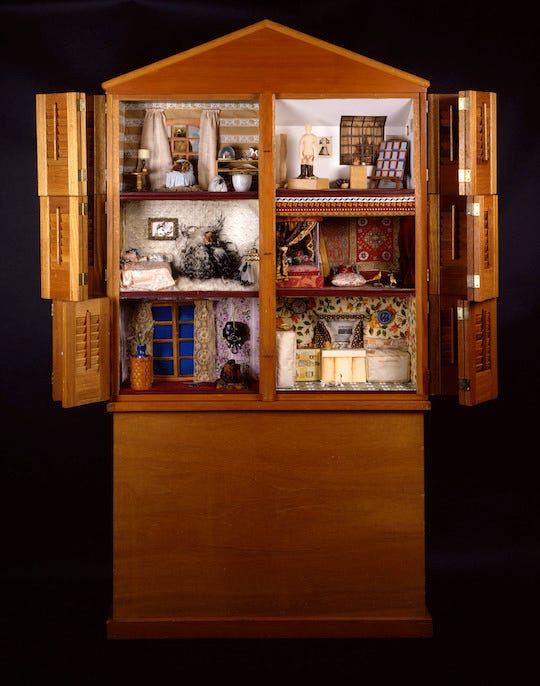

Dollhouse, Miriam Shapiro, 1972 (above, as lead image)

Dollhouse was part of Womanhouse, Shapiro’s legendary 1972 exhibition with Judy Chicago and students from the feminist art class she and Chicago taught together. It’s now part of the Smithsonian collection and on view in their North American art wing. Womanhouse, and by extension Dollhouse, was meant to “radically question” the dominance of men in the art world. In Shapiro’s mix-media house, a well-appointed home reflects a domestic ideal — but the artist’s studio, usually a male space, is here intended for the woman of the house, a place of creative liberation. It’s a “room of one’s own” made manifest. However, 50 years later, Dollhouse also speaks of privilege, and its role in an artistic life: the ability that I have, as do many of my peers, to write in comfort and relative luxury. As we move into whatever comes next, it’s a reminder of both the necessity to carve out spaces for creativity, and the inherent difficulty in doing so for many women.

My Mother Named Me Beloved, Kalila Ain, 2021

My Mother Named Me Beloved is a gorgeous, evocative depiction of motherhood. The detail of the girl’s goggles, slightly askew; the sunlight on their faces, the blues reflecting the nearby water. I saw this painting last fall in the Rest Is Power exhibition at NYU for The Black Rest Project. It resonated with me for multiple reasons, and I’ve thought of it often. However, this week across social media, I’ve seen multiple black, American female content creators - including Portia Noir and Luvvie Ajayi Jones implore white women to leave black women alone to process their grief and anger. The idea that black women — almost 90% of who who voted for Harris — should be the emotional sherpas for aggrieved white women is appalling. While several of these creators aren’t moms, and their posts have nothing to do with motherhood, their requests underscore the importance of The Black Rest Project, and why it exists at all. Black womanhood and motherhood have been under continual assault for all of American history and it will get worse — Kalila Ain’s painting depicts how normal, peaceful, and beautiful it can and should be.

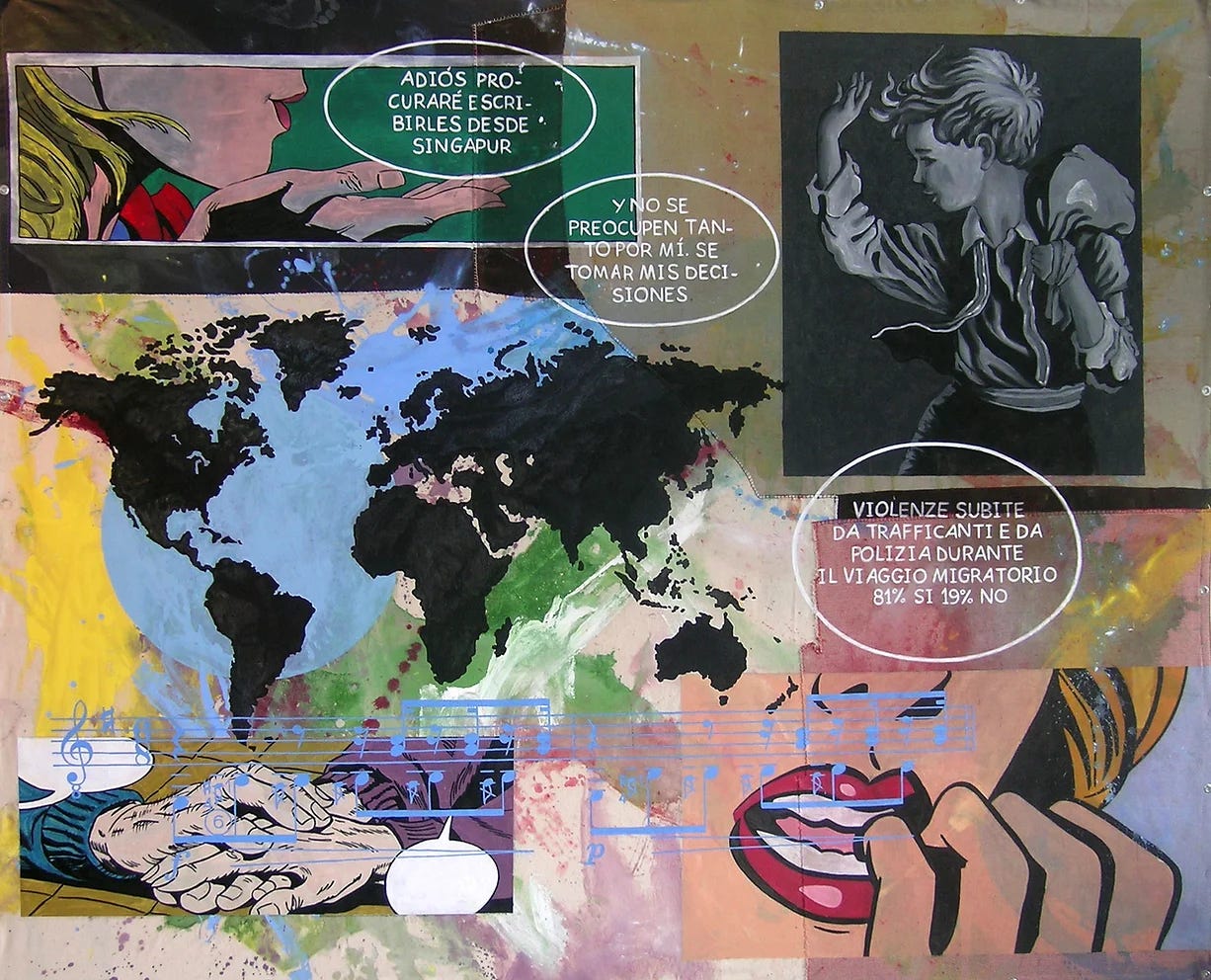

Usyn II, Almudena Rodriguez, 2017

Rodriguez is Spanish and lives in Madrid — she’s the only non-American woman on this list. I interviewed her in 2021, ahead of an exhibition at Chicago’s PAGODA RED. Her incisive, compelling thoughts on global immigration were deeply affecting and are the catalyst for much of her art. Rodriguez has spent extensive time on the border between Texas and Mexico, living as “an immigrant with papers” among immigrants without them. She often incorporates fabric from the tarps used in refugee camps into her canvases. Rodriguez notes that “I explore [immigrant’s] relationship to space, the one they are leaving, the one through which they pass, they long for, and where they are arriving, as well as their relations with others – a relationships full of tolerance and hostility.” The border crisis has been ongoing, and frequently inhumane under multiple administrations. Usyn II — with its stats on violence, pensive women, clasped hands and waving child — is a deeply felt, wide-ranging encapsulation of the immigration and refugee crises that will only worsen with climate change and authoritarian governments.

Sustaining Traditions—Digital Teachings, Kelly Church, 2018

I learned about Church and her work when ARTnews chose Sustaining Traditions—Digital Teachings as one of their 20 works not to miss at the Art Institute of Chicago. I’m fascinated by and collect handmade baskets, so I went find it on my next visit to my favorite hometown museum. In person, it’s stunning. Church is a Pottawatomi/Ottawa/Ojibwe woman who “comes from an unbroken line of black ash basket makers and from the largest black ash weaving family in the Great Lakes region.” The black ash she weaves into baskets is directly threatened by climate change and by the Emerald Ash Borer, an invasive insect. In Sustaining Traditions—Digital Teachings, she not only continues the basketweaving tradition in the present, but look to an uncertain future: inside the basket is a flashdrive that contains traditional knowledge for future generations. The basket is a tie to history, to the connections between Church and her ancestry. It’s also, explicitly, a time capsule to the future, a means to preserve indigenous knowledge. It’s an emotionally resonant reminder that cultural traditions and the environment are often entwined — and are simultaneously under threat.

The Flag is Bleeding #2 (American Collection #6), Faith Ringgold, 1997

I saw The Flag is Bleeding #2 at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 2019. It was surreal to confront my own country’s brutal history while abroad, especially in a time of deep global unease under the last Trump presidency. American quilting has long been a generational art, passed down by mothers. The lauded quilters of Gee’s Bend trace their distinctive patchwork patterns back to their enslaved ancestors in the early 19th century. Here Ringgold paints a “quilt” that subverts a domestic art form to depict the violence imposed on black American women, as their blood and the blood of their children drips onto a flag symbolizing freedom and democracy. The Flag Is Burning #2 is centered on black motherhood, which is crucial to its meaning and impact. Still, in a post-Roe v. Wade America driven by Christian nationalism, Ringgold’s depiction of a mother bleeding on the flag is likely to transcend, to become an indelible impression of American motherhood as a political casualty.

In the next few years, women will continue to create work that is incisive and smart and moving. Hopefully, as we process what the Trump administration can and will do, we can continue to envision a future where all woman can create art from a place of security, joy, and true freedom.

How have you processed the election so far? Please free free to share any artistic works that have or continue to resonate with you.